Resource: https://ucdavisdatalab.github.io/workshop_keeping_data_tidy/

Overview

This workshop introduces learners to best practices for data entry and organization for data-driven projects. With interactive, hands-on examples we’ll practice using data validation tools including filters, controlled vocabularies, and flags in Microsoft Excel. These skills are also applicable to working in Google Sheets, LibreOffice, and other spreadsheet software. At the end of the workshop, learners should be able to identify the best practices for designing a spreadsheet and entering data, compare different data formats, and be able to use spreadsheet software for basic data validation. This workshop is designed for learners who have basic familiarity with spreadsheet programs. No coding experience is required. All participants will need a computer with Microsoft Excel 2016 or newer, and the latest version of Zoom.

Introduction

Learning Objectives

After this workshop, participants should be able to:

- describe the steps in the lifecycle of a data-driven project

- identify best practices for entering and formatting data in spreadsheets

- use tools in Microsoft Excel for data validation and filtering

- define restricted vocabularies, data dictionaries and filter keys

- compare the advantages of different data file formats

Before Excel: The Data Lifecycle

Before we begin entering and organizing our data in spreadsheets, we consider the paths our data takes as it moves through our data-driven project as a whole. Where does our data come from? Where is going, what are we going to do with it? Who is it ultimately for? Data scientists call this process the “data lifecycle”.

Note: There are many different versions of the data lifecycle, but we particularly like those of the US Geological Survey and DataOne. Our data cycle steps below are based on both of those sources (Image Source: USGS)

The steps of the data cycle:

- Plan: plan what data will be collected, how it will be processed, analyzed and stored throughout the project

- Acquire: collect data, through measurement tools and observations, (i.e. survey instruments, interview transcripts, GPS location loggers, molecular sequencing assays, behavioral observations, etc.) and enter the data in digital form

- Process: process data to assure quality, clean and format the data for downstream analyses and storage

- Analyze: explore and interpret patterns in data, summarize and visualize results, test hypotheses using statistics, and report conclusions

- Preserve: store data in secure way and in formats that ensure long-term accessibility and reuse

- Publish/Share: distribute data through peer-reviewed publications or submitted reports, and archive data in field-appropriate data depositories/archives for future access and analysis.

The following processes occur throughout the data lifecycle:

- Describe : document sources of data, keep records of analysis or processing throughout all steps, record keys to codes and dataset-specific variables, and log history of dataset use.

- Manage quality : follow best practices at all steps to ensure quality, transparency and reproducibility throughout the data process.

- Backup and secure : back-up and secure data in reliable, accessible storage locations at all steps of the process

When working with Excel, many of us are often at “Acquire” and “Process” stages of this lifecycle. In this workshop, we will illustrate best practices that will help with first-time data entry (Acquire), data validation, cleaning and filtering (Process) as well as discuss formats and version control that will help with preserving data for reuse and accessibility (Preserve).

Interested in documenting your data?

In an upcoming workshop (March 4th, 2021), we will be discussing metadata and documentation for data-driven projects. This workshop will delve more into the Describe process at all steps. (See here for more information.)

Spreadsheet Best Practices

In this section, we list some of the best practices to follow when entering and arranging data in Excel. These quick tips will help with data analysis and interpretation down the line, making your data more shareable and reproducible.

The data for the examples comprises historical data on women of color in the U.S. Congress, and the “dirty” version shown can be accessed here.

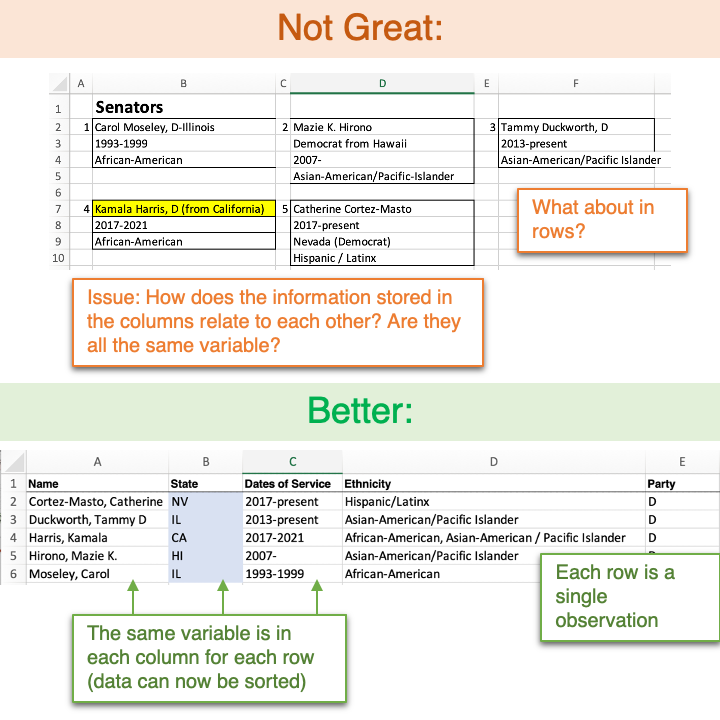

1. Keep variables in columns, observations in rows.

In a spreadsheet (or data stored in a tabular format), the smallest “unit of measurement” is a cell, such as cell A1. It is best practice to place your variables in columns, and separate observations in rows. In this “coordinate” format, all cells represent the intersection of an observation and a variable (i.e. the value of that variable for that observation).

Why do this? This is consistent with the format of many other data processors, such as more formal, SQL-based relational databases and the “tidy” format that facilitates programatic analysis in languages like R or Python. For more on this, see #2.

Examples:

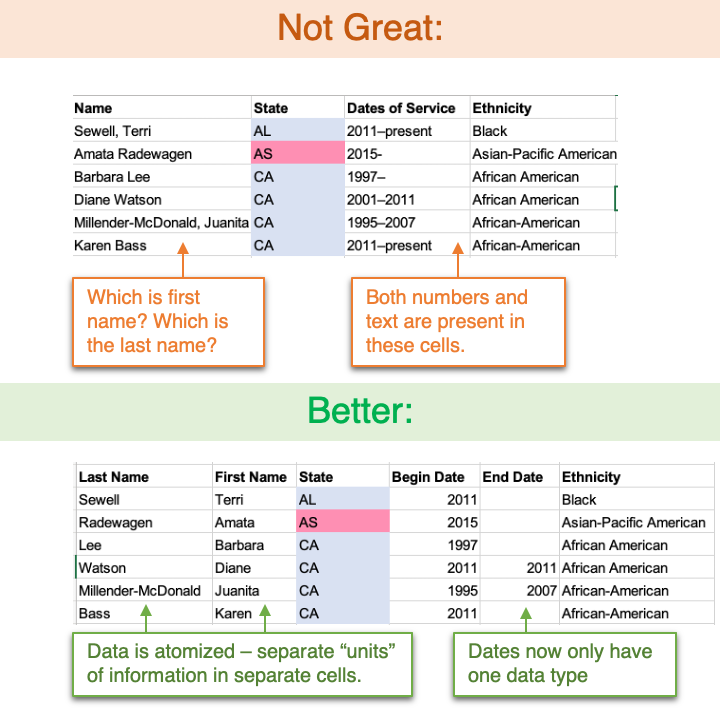

2. Stick to one datatype per variable/column.

With your variables in columns, it is best to stick to one datatype per variable. A datatype defines what kind of data is being stored, such as numerical data, integers, text or character strings, or dates, for example. As you define your variable columns (as in #1), ask yourself: What would the data type for this column be? For example, date_of_birth would be a date, distance_km would be a number, question10_response may be a character string of text.

Considering that the cell is the smallest “unit of measurement”, each cell in the variable column should ideally be of the same type, and should contain only that type. If you find that some of your cells have multiple types within them, it may be worth creating a new variable/column to store and differentiate this data, such as a “unit” column, or a “notes” column (see #3).

Lastly, make sure that you aren’t inadverently storing multiple “units” of information in one cell, even if they are the same type (e.g. numbers). Some common examples are including birth and death dates (a range) in one cell, or latitude and longitude in the same cell in a column.

Why do this? This will facilitate analyses down the line. Have you ever tried to sort a column in Excel and gotten the annoying error that asks you to “sort everything that looks like a number like a number”? This will helo avoid this issue, but will also allow you to accurately use functions like sort, calculate sums, averages, and run analyses on variables as separate units, without having your data be “polluted” by excess information. Further, if you end up programmatically analyzing your data using languages (like R or Python) or other data processing software, you may lose data that does not match the type exported, or experience errors where these mismatched types are converted into new values or into NAs.

Examples:

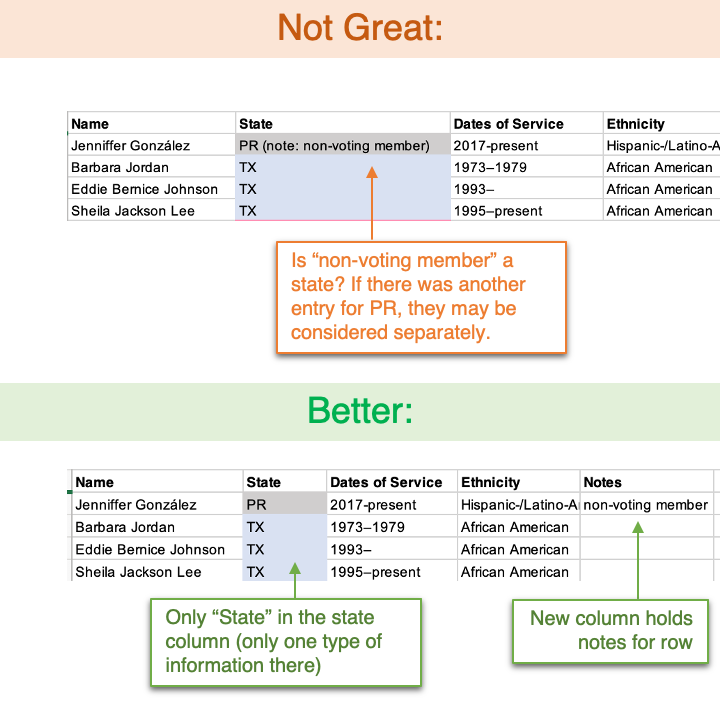

3. Add notes and comments in separate columns.

Given that we should enter one data unit / type into our columns (above), a common follow up is: What about notes, though? Of course, it’s important to include notes, comments, and disclaimers about samples or observations. However, including these directly in your cells along with data points will lead to problems downstream in analysis. As a solution, create a new column called “notes” or “comments”. If you’d like to restrict notes to certain variables, you can have multiple notes columns, and include the specific variable they refer to in their column names.

It’s best to avoid

- adding notes directly in cells with your data points

- This includes asterisks, or “see notes” notes!

- using the hovering comments function found in “Review”

- This will be lost outside of Excel (see below about non-proprietary formats)

- They’re also difficult to find without hovering over cells

- using color-coding to highlight issues or questionable cells

- see #4

Why do this? As in #2, this avoids multiple types in cells that can muck up downstream analysis or imports into programming languages or other software. For instance, your computer doesn’t understand that “Alaska (note: pre-statehood)” is the same as “Alaska” in terms of analysis. By keeping notes separate, you keep variables “atomized” and organized into the smallest units of information, helping your collaborators (including future you!) find information easier.

Examples:

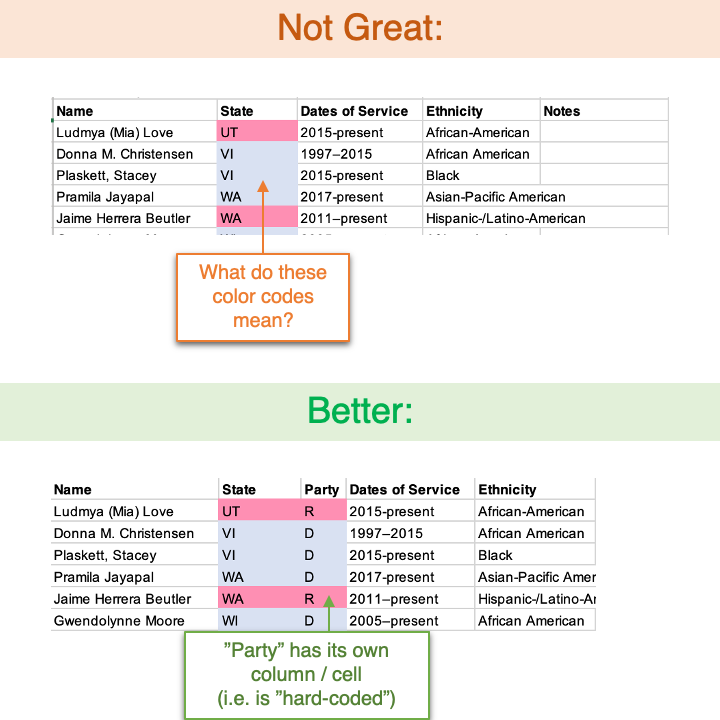

4. Code information explicitly in cells rather than in formatting.

While using color codes, bold and italics to indicate information about data points is tempting, it is best to avoid actually coding information in formatting. Instead of using color codes, “hard code” this information explicitly in its own column. Note that it is OK to use color codes to help draw your eye, visually sort your data, or flag values, but it’s critical that the information in color codes is also hard-coded into an actual cell.

Why do this? Data included in these formatting is not made explicit (i.e. is not stored in a cell, in a recognizeable data type). These data will thus be hard to analyze (how do you search for or sort by a color?). Further, formatting is Excel- or spreadsheet-specific and will be lost when exported to other programs (see #8.

Examples:

5. Be consistent with variable codes, formats, and units.

Often, variable levels or categories may be very long, and during data entry, you may want to use abbreviations or shorthand to make data entry easier. This is fine! But if you choose to use codes, make sure to do two things:

- be consistent, using the same codes and formats across the entire column and all your associated datasets; and

- record the full code names in your data documentation (often referred to as metadata, your data about your data). (To learn more about metadata, see our associated workshop.)

For numerical measurements, also be sure to keep units consistent. Is your latitude / longitude entered in minutes/seconds format or in decimal format? Are your weights entered in pounds or kilograms, distance in miles or kilometers? It can help to include the unit in the column name, so you know to enter data in the correct units.

Why do this? Consistent codes within variables/columns will make downstream analysis, such as trying to sort or summarize data based on levels of a variable, easier. Keeping variable names (i.e. your column names, the top row of your spreadsheet) consistent across datasets or spreadsheets will make joining these datasets together straightforward in future analyses. All of this will improve the interpretability of your data for collaborators and your future self, increasing transparency and reproducibility.

Examples:

6. Store one dataset per file.

Avoid “stacking” multiple datasets (i.e. observations with different variable or column names) within one spreadsheet. This also confuses the computer / Excel, which considers one row an observation and one column a variable (see #1). Move these separate tables or datasets to their own file, or combine them using more columns or rows.

While Excel allows you to use different tabs within one Excel document, it is best to save separate datasets as separate files. It’s okay to use a new tab as a sandbox for exploratory analyses, but ultimately, if you want to save data for future use, save it in a new, separate file.

Why do this? The datasets hidden in separate tabs aren’t easily searchable in your folder directory, and may make it hard for collaborators or your future self to find this data. Further, non-proprietary formats, which are better for storage, sharing and analysis in programming languages, do not support multiple sheets per file (see #8).

7. Keep your data “raw”.

Always, always, always save a copy of the original (“raw”) version of your data. Adding “original” or “raw” as a suffix to the filename can be helpful for you to remember the origin of the file. If data cleaning is necessary, save a new version (you can add the suffix “raw_cleaned” to the filename). Avoid doing any analyses or further processing in these versions. Instead, create a new file to do these further processing or analysis steps (you can call it “processed” or “analyzed”).

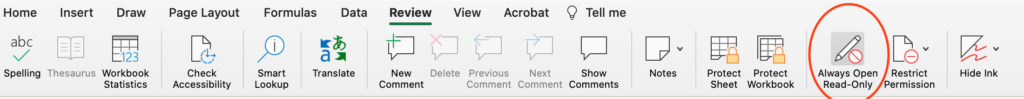

Pro tip: if you’re working in a spreadsheet program like Excel, make your origin/raw data read only. This forces future you, or any collaborators, to have to make a copy in order to edit it.

How to make a file read-only in Excel 2016+:

Go to “Review” tab, and select “Always Open Read Only”.

Your file should always prompt the next user to open read-only from here on out. If you would like to fully restrict your file, you can protect it with a Password (Restrict Permission).

Why do this? This will help you preserve your data as intended, and avoid any accidental formula edits, pull-downs, or unintended changes that cause the original data to be corrupted or lost.

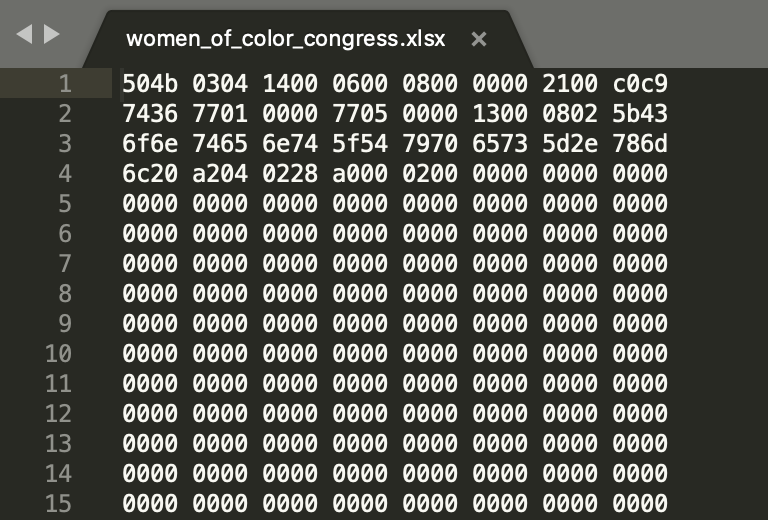

8. Save your files in a non-proprietary format.

As great as Excel is, it is Microsoft’s proprietary software that does not translate to long-term data storage or cannot be read by many other data management / database systems or programming languages. For longevity of your data, store your data in a non-proprietary (“open”) format, such as:

- .csv: comma-separated values. Cells in columns are separated by commas across the rows. Good for most quantitative uses, may be problematic for text data with full sentences and strings that include punctuation like commas.

- .tsv: tab-separated values. Similar to .csv, but cells are separted by tabs. A better alternative for data types that include commas and other punctuation.

Why do this? Have you ever tried opening a .xlsx file in a text editor? It looks something like this:

All of your data is obscured this way! These files are not accessible to many other data processors and managers, nor are they easily importable into programming languages like R for downstream analysis. While you might currently have access to Excel, you may lose access in the future, or may have collaborators without access to the software. Using non-proprietary formats increases the longevity and access to your data. In fact, many field-specific and governmental data archives are requiring data to be deposited in non-proprietary formats. Further, these “open” formats work better with version control softwares, like git (see next, #9).

9. Control your versions (or they will control you!)

As your project continues, you will likely collect data multiple times, add data, and end up formatting and processing your data in many ways. In addition to keeping your data raw, you should keep the different iterations of your dataset, or versions, delineated. This process of storing multiple versions or iterations of a file is called version control.

One of the simplest ways to implement version control is to have a naming system, where you add some information about your new file, be it the date or additions, to the name of the file, along with the date it was saved. This “by hand” method can work well for some users’ needs, but it can also become messy and difficult to navigate, as seen here:

Consistently using the same naming scheme can help you manually track your versions, and avoid later headaches when you can’t remember which document you should be working on – “final final” or “final v2”???

How to name your files

Filenames should be both human and machine readable, and play well with default ordering. Most importantly your naming scheme should be easy for you and your collaborators to remember and implement consistently.

Human readable filenames contain useful information regarding the file content that can help you identify the file you want without having to open it. The origin date and/or provenance of the file, study system or author name, brief “slug” description of what was performed on the data, and the date the file was processed can all be useful to include in the filename. Starting the filename with something numeric (i.e., the dates) will harness default ordering to display your files in a logical order on your machine (example, 2021-02-08_workshop_tidy-data or 01_workshop_tidy-data, vs tidy-data_workshop_2_08_2021). For dates, use ISO 8601 standard (YYY-MM-DD) to ensure chronological ordering and make it easier to share files with international collaborators. Similarly, for numbers make sure to “left pad” them (01 vs 1).

Machine readable filenames are structured so it’s easy for your computer to search for the files later and for other software programs to import the files successfully. To facilitate this avoid spaces, punctuation, and accented characters in your filenames.

Decide whether to consistently use dashes (this-is-my-awesome-file), underscores (this_is_my_awesome_file), or camelcase (ThisIsMyAwesomeFile). Do not rely on case sensitivity for your naming scheme (thisismyAWESOMEfile and THISISmyawesomefile are two different files). We prefer dashes or underscores (or a pre-determined combination of the two) because it helps the filename to be easily human readable. It also allows us to programmatically recover metadata from the filenames (i.e., using regex or scripting in a program like R or Python). For example, you can use underscores to delimit units of meta-data, and hyphens to delimit words (this-is-my_awesome-file or 2021-02-08_workshop_tidy-data).

For similar data files, or versions, you can use ‘globbing’ to make it easier for you and your computer to find relevant files (e.g., 2021_workshop_tidy-data.Rmd, 2021_workshop_text-mining-NLP.Rmd, and 2021_workshop_intro-Python.Rmd can all be quickly found together becuase they contain the prefix of “2021_workshop”).

Regardless of what scheme you pick, stay consistent and it will make your work much easier!

Version control software can do it for you

If manual version control works for you, great! As you start working on larger and more complex projects, particularly ones with multiple collaborators, it’s worth exploring a programmatic version control approcah – using software that can track your versions (and what’s changed within them). This can faciliate your ability to collaborate with others and quickly revert to past versions or incorporate changes from multiple versions into one primary document. Git is a popular free version control software, which you can learn more about how to use in DataLab’s upcoming workshops.

10. Document your data.

Lastly, as mentioned, it is important to describe and document all the decisions you make with your dataset. This data about your data is called metadata.

From the above tips, you’d want to document details about your:

- Column names within a dataset

- What do they stand for?

- What data type should they be?

- What is their source? Can these data be shared?

- Variable codes within columns

- What do the abbreviations in your columns stand for?

- What are the acceptable values for a variable? How many levels are there?

- How are missing data indicated?

- Datasets

- How do datasets, if there are more than one, relate to one another?

- Which are the “original” or “raw” data files? Which have been processed or cleaned, and if so, how?

- What code or filters did you use?

The answers to these questions can be stored in a README.txt file that follows along in your folder directory, acting as a “buddy” to your datasets, code, and the files it describes. No dataset should go alone without an accompanying README or documentation!

For more information about metadata and data documentation, we will be holding another virtual workshop in March on this topic (registration for Zoom link required).

Principles to Practice

Data Validation

Data validation is a critical aspect of the research data lifecycle. It is the often ongoing process of ensuring the accuracy and quality of your data so that they are useful and can be analyzed. Employing validation rules (or checks) both before and after entering your data can help you ensure that your data are logical and fit necessary parameters. One common example is controlling numerical values so they fall within expected bounds (0-1 for a percent, for example) and that levels for a character data type are standardized and spelled correctly (percent vs Percent, per, or %). Leveraging built-in tools in your spreadsheet processor to automate validation logic and populating data dictionaries at the start of your project can help reduce the amount of subsequent necessary data cleaning. It can also help identify suspect cells after you’ve finished entering your data.

Some important data validation checks you should always perform on your data are:

- Data-type check – only expected characters are present in a field (ex. numbers only accepted for numeric, text only accepted for character types)

- Format check – data are in a specified format (ex. dates must be formatted as YYYY-MM-DD)

- Range check – data are within a specified range of values (ex. the range must be 0-1 for a percent)

- Code (or levels) check – data are consistent with one or more external rules (ex. experimental condition can only be ‘placebo’ or ‘treatment’, spelled correctly and case sensitive)

- Consistency check – entries across fields are logical (ex. the date of death cannot be earlier than the date of birth)

- Uniqueness check – each value is unique (ex. each subject, or row, must have a unique ID number)

While for reproducibility and scientific integrity purposes we encourage researchers to validate, clean, and process their data in coding-based software (like R or Python), Excel is a commonly used and powerful tool. It “Excels” at being straightforward for onboarding new research assistants to enter small-ish, simple datasets. And you can leverage its built-in data validation tools (discussed below) to help ensure higher quality data capture.

Data Validation in Excel

We’ll use the tidy version of the Women of Color Congress dataset to practice a few different different data validation tools in Excel.

Demo dataset: 2021_workshop-tidy-data_demo_woc-congress_clean.xlsx

Try the following in the demo dataset:

Data-type, Range and Format validation: * You can format the cells to force them to contain a specific data type. Right click on a cell (or column) and select format cells. To constrain to numeric values, select “Numeric.” For values that should have a certain number of digits (like a year, or if you want to add a leading zero), select Custom and edit the Type field to contain the number of zeroes corresponding to the number of desired digits (i.e., Type would be 0000 for a 4-digit year). * You can also use the data validation tool under the Data ribbon to constrain to a data-type. Using the numeric type as an example, under Data Validation-Settings select to allow a ‘Whole number’ between a known minimum and maximum range will help prevent typos and incorrect entries. You can add an “input message” to help those entering the data remember what should go into the cell (such as “this entry should be a 4-digit year”), and an error alert (such as “this entry does not match the cell parameters for a 4-digit year”) to alert when errors are entered.

Consistency validation: * You can also use data validation such that the entry in one cell depends on that of another. For example, Year Term Began should always be prior (or smaller numerically) than Year Term Ended. Under Data Validation-Settings select to allow ‘Custom’ and enter a formula where the column for Began is less than the column for Ended (=F1<G1). * You can use the Data Validation “Circle Invalid Data” setting to help you quickly identify the pre-entered errors in a dataset, but note that it may also flag your headers, in which case it’s helpful to remove the data validation for those respective rows.

Code validation: * The “Filter” tool under the Data ribbon is a helpful tool for inspecting the levels of a variable. Highlight the header row and select filter to see a dropdown of the unique entries within each column. This can be helpful for identifying misspellings or typos, particularly in small datasets. * A robust approach is to develop a data dictionary with a restricted vocabulary list that you can use with Excel’s data validation tools. A quick way to do this is to create a new tab that contains lists for all the levels of your variables. Once created, highlight the column of interest in the spreadsheet and select to allow a “list” on the Data Validation-Settings. In the Source field, highlight the list (excluding the header) on your dictionary tab. Add input messages and error alerts as appropraite to help those performing your data entry.

Conditional Formatting: * You can also create rules using Conditional Fomatting, under the Styles group on the Home tab, to quickly highlight all appearances of a specific string within cells. To implement, create a new rule to “format only cells with specific text” “containing” and enter your string of interest.

Practice!

- Constrain Year Term Began to be a numerical value between a logical range.

- Constrain Year Term Ended to be a numerical value greater than Year Term Began.

- Constrain State to be a 2-letter code corresponding to a US state or territory.

- Constrain Party to be a code corresponding to the 3 known levels of party affiliation in the dataset.

- Use conditional formatting to find all NA values in the dataset. What worked? What went wrong? How might you fix it?